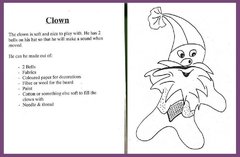

‘Deeds, not words’. The VSI motto summarises the can-do attitude and hands-on approach to problems and volunteering typical of the organisation. Volunteers and organisers lived up to this philosophy, as shown by an innovative workcamp: Toyzone. It took place in late August and September 1998. In the space of just two weeks, the participants successfully accomplished three related, but distinct tasks: first, they made toys for disabled children, mostly from scratch and by using recycled parts and materials; second, they produced a booklet, for parents, containing detailed instructions on how to make toys suitable for disabled children; and they curated an exhibition to raise awareness of the issue and of the project itself.

August and September 1998. In the space of just two weeks, the participants successfully accomplished three related, but distinct tasks: first, they made toys for disabled children, mostly from scratch and by using recycled parts and materials; second, they produced a booklet, for parents, containing detailed instructions on how to make toys suitable for disabled children; and they curated an exhibition to raise awareness of the issue and of the project itself.

As put by a workcamp participant, ‘children learn to use their body, improve their mental, social and language skills by playing’. And disabled children are no different in this respect: playing is vital to their development also. As the auntie of a disabled child myself, I have often experienced a sense of powerlessness and frustration when it comes to choose a toy for my nephew in toyshops. Things must have been even worse back in 1998, at the time of this workcamp. Mainstream toys, being often made with exclusively non-disabled children in mind, pose many barriers for disabled children to use.

That’s when Toyzone came in: in a synergic and long-sighted way, it provided the answers to various needs, promoting inclusiveness in the broadest sense. By combining a number of skills, experts and eager-to-learn volunteers paved the way for future developments in an area that had been often neglected in the past.

Among the many activities they engaged in, the volunteers learned to see the world from the perspective of a disabled child: they played a game, led by an occupational therapist, in which they imagined that they had no legs, and they had to reach for their toy.

They spent a weekend camping in Glendalough. The hostel there was not accessible, so it was difficult to accommodate Branca, one of the volunteers. But, in the words of a workcamp participant, ‘We had to build a ramp for her but we got quite good friends with other people in the hostel who helped us’.

The whole workcamp may be summed up by the following comments:

‘Everybody had eventually made at least one toy or switch (…) when we started to organise the exhibition and booklet. This was one and a half day before the exhibition! So we ended up working the whole night, photocopying, writing, painting the posters for the exhibition… But it was fun.’

Parents of disabled children visited the exhibition, as well as the adviser of the Minister for Disabilities.

Toyzone ticked four main social justice boxes: inclusiveness, DIY, sustainability, and cultural exchange. The principal aim of the programme was to provide, and teach how to make, toys suitable for disabled children. Those children, who often find it difficult to play with regular toys, were now given the chance to play with tailored-made toys. DIY comes in because most of the toys in the exhibition were made from scratch. Surprisingly, some toys are relatively easy to make, and affordable too—again meeting the inclusiveness need. DIY also promotes community spirit, since if you are in difficulty yourself you are likely to ask a family member, neighbour or colleague for help. Sustainability was also taken into account by Toyzone, for most of the materials used to make the toys were recycled or donated—this at a time when recycling was almost unheard of, before it became mainstream. Finally, the workcamp involved extensive cultural exchange: the volunteers who took part—ten in all—came from many different countries, both in Europe and from further afield. They visitedDublin, made new friends, and learned new skills.

Toyzone was ahead of its time: it was a trailblazer, which helped to shine light on often neglected issues, and pointed towards possible solutions; it promoted generosity and an openness of mind and heart. It taught that with some ingenuity, will to bring people together and learn new skills, it is possible to make or adapt toys for disabled children.

Tiziana Soverino